And so, dear gardening friends as we continue to ring in 2013

with the garden at its drabbest, instead of

withered leaves and a few

cold looking hellebore buds,

I offer you -

A NEW YEAR’S TREAT

It’s difficult to dream up a delight special enough to charm

my wonderful and loyal readers at the beginning of a new year.

And might I take this moment to say how much I appreciate those wonderful little splashes of heart warmth when one of you pops up and tells me

that you look forward to opening DIRTIER,

or reminds me of a little insight I might have even forgotten

because you read it here.

Very encouraging…and what is more important than encouragement…

So, I present to you one special woman’s fabulous fable

of a mythical bird.

The woman happens to be my partner, Lys Marigold, and I know that

if you are a fan of DIRTIER, then you will relish this…

THE SECOND HOOPOE

A revisited essay by Lys A. Marigold

We harbor within us an ancient urge to order the world. A mythic impulse, as old as Methuselah, to put names to every little creature and beast. A basic mathematical need to codify and condense, to create harmony. All that is satisfied when you spy a rare bird.

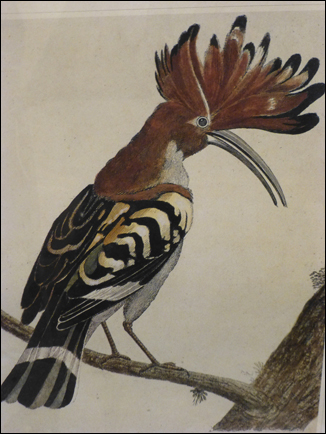

On one of the first days of the first trip to the red ruins of Petra in Jordan,when walking past a clump of cotton-candy pink oleanders, I heard a loud and repetitious cry, “oop-oop-oop.” Perched on an inside branch was a regal bird,made slightly comical by a coppery head ringed with black-tipped plumes, much like an Indian chieftain’s war bonnet.

If my initial reaction to this particular bird was being in awe of something so

beautiful, the second was to use my detective instincts to track down the

identity of this rara avis. Luck was on my side – or ‘gismih o naseeb’ in Arabic, meaning more than just luck…destiny. That night in the hotel lobby I spotted a poster illustrating the birds of Jordan, including one that was said to navigate

by the sun on its annual sojourn.

It was a Hoopoe (Upupa epops) or in Arabic, Hudhud – an uncommon bird

of passage which flies with a smallish wingspan (18 inches/45 cm) from England

to Africa and back, seeking warmth and abundant insects.

With jail-cell black and white stripes on its wings and tail, a smoked-salmon color body and a long, pointy, down-curved bill, the hoopoe’s most distinguishing feature is an erratic flight pattern, zigging and zagging like a butterfly. The hoopoe and all its hues and cries sounds like a silly invention of nonsense poet Edward Lear, similar to the “Dong-with-the Luminous-Nose.” And because it is notoriously hard to photograph by bird watchers, its name is used in British society to describe a precious object as, “O, it’s so-o hoop-ooe,”

Legend has it that hoopoes were first given crowns of gold as a reward for sheltering wise old King Solomon from the parching sun. Hunted almost to extinction for their valuable golden diadems, the hoopoes appealed to the King (who, as you may remember, understood the language of all animals) to change the crown to a crest of feathers. Mission accomplished, henceforth hoopoes were known as “the children of Solomon.”

These birds belong to the Coraciiformes order of cavity nesters who find homes in the holes of trees or tucked away in the crevices of crumbled antiquities. Whether the result of the close-quartered nesting habits or the fact that a musty odor exudes from the female’s preen gland, hoopoes, whose flesh is edible, are listed as no-no’s on the list of what’s kosher in the Old Testament (Lev. 11:13-19).

The hoopoe is a nomad, in the truest sense of the word.

Dictionaries are misleading when they suggest random movement or “roving” as the definition of “nomad.” Nomad actually comes from the Latin/ Greek nomas, meaning “to pasture,” or follow a known route of abundance. As the B’dul Bedouins (possible descendants of Petra’s vanished inhabitants, the Nabataeans) did when they moved their flocks at the change of seasons, shifting from hilltop to valley in search of water and tender greenery. This pastoral routine was the reason I happened to be near the Siq al-Barid one June, using my four-wheel-drive to bring supplies to an old tattooed woman who still pitches her summer tent amidst the cooler rocks.

On that fateful day, while creeping slowly over the deep ruts on a “track” cut through the parched white hillocks, I noticed a blur of movement to my right, a definitive flicker of feathers from a bleached terebinth branch -- and froze in place. One close listen to its avian chatter pinpointed the caller: it was oop-pupping away – identifying it instantly as a migratory crown prince, my second Hoopoe.

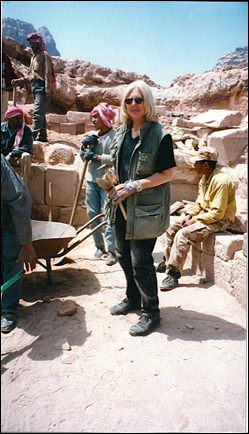

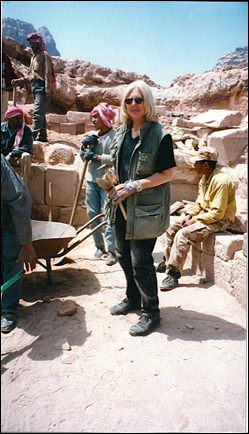

I like to imagine myself as a descendant of the grand tradition of women travelers who came to the Ancient Near East following the footsteps of adventure.

Intrepid sojourners who left a trace on a primitive Petra, such as Jane, the Marchioness of Ely, lady-in-waiting to Queen Victoria who in 1870 wrote under the unisex J. Loftus, as so many women did; and even Agatha Christie put this understated passage in Appointment with Death, 1938, “Have you not been to Petra, M. Poirot?...It has an – how should I say it? – an atmosphere.”

Although I experienced a few spine-tingling frights – being caught in the crossfire of a rebellion (army roadblocks, burning trucks, food shortages) and being bitten by a scorpion while I bedded overnight miles away from help, in reality, mine was more of a danger du jour. In the isolated ravines, disturbed only by a brilliant blue lizard or soaring Barbary falcon, I explored solo, seeking old carvings and rock art. Finding toeholds to climb up the steep cliffs was relatively easy, but when it came time to go back down, getting myself to dangle over a sharp precipice and search blindly for a cleft in the rock for my foot was heart-pounding.

And fool-hardy. Especially when everyone had been warned about a young American tourist who had hiked up the 808 steps to the Monastery, gone out on the top of its massive façade and slipped to her death. “Those are the risks,” I said to reassure myself. The lure of the unpredictable sharpens the senses. Like the snap of fingers for someone hypnotized, this adrenaline jolt wakes us up from our civilized trance and puts us on alert.

When you stop being complacent, you fall back on instinct. My eyesight “improved” day by day, as features came into sharp focus. Along the ridges of smooth-sided boulders, it was suddenly possible to isolate the many signs of man: feathery hack marks on the rocky walls; loopy Nabataean writing; elemental god-blocks with stylized faces; high altars with humble libation niches; crisply carved rosettes and crescent moons that paid homage to the guardian goddess, Al Uzza, The Mighty One.

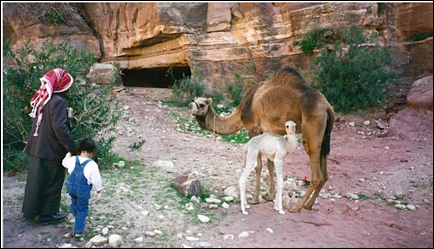

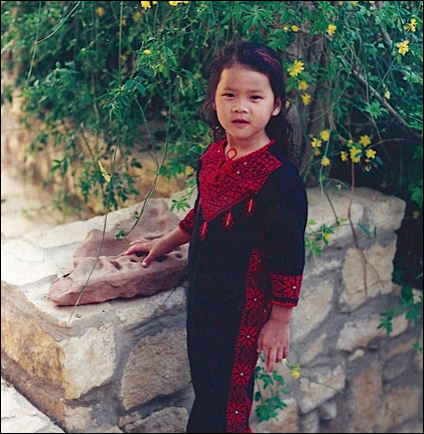

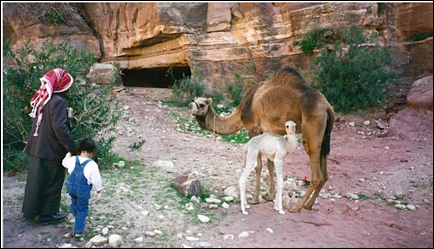

To catch the true light before the scorching sun turns the russet dust into blaring whiteness, you need to go out before dawn. The desert landscape that seems barren and empty, is, in reality, blooming ferociously – with wild dwarf black irises, white-flowered broom, opalescent green sage (shiah), scarlet ranunculuses, masses of maidenhead ferns, entwinements of magenta morning glories and giant dark purple onions. The desert floor is laced with sherds of fragile, finely painted pottery that crunch underfoot as you walk. What appeared in the distance to be a landlocked swan with its long undulating neck turned into a milk-white baby camel on its knees, the perfect size for my warrior-baby, Skye Qi, to ride. And ride she did, holding on to brightly-dyed, woven goat-hair reins.

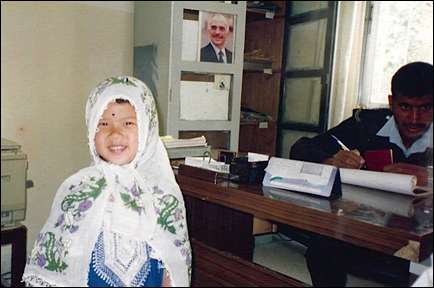

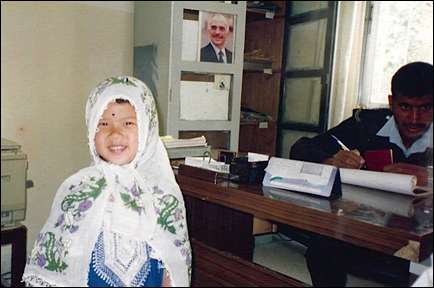

( I interupt this wonderful tale to draw your attention to the sweet little girl Skye

being led by her bedouin 'nanny' to ride the baby white camel...which is not the

usual color of new-born camels...making this an even rarer occassion...DB)

Being visited by not one, but two hoopoes seemed to be profoundly symbolic that my path was pointed in the right direction: a reverie to the wild spark of travel and a cognitive map to infinite possibilities.

Wasn’t that great?

I think Upupa epops is the crowning glory of

all Latin, botanical and otherwise, that I have ever heard.